DIS-TANZ DIARY #12

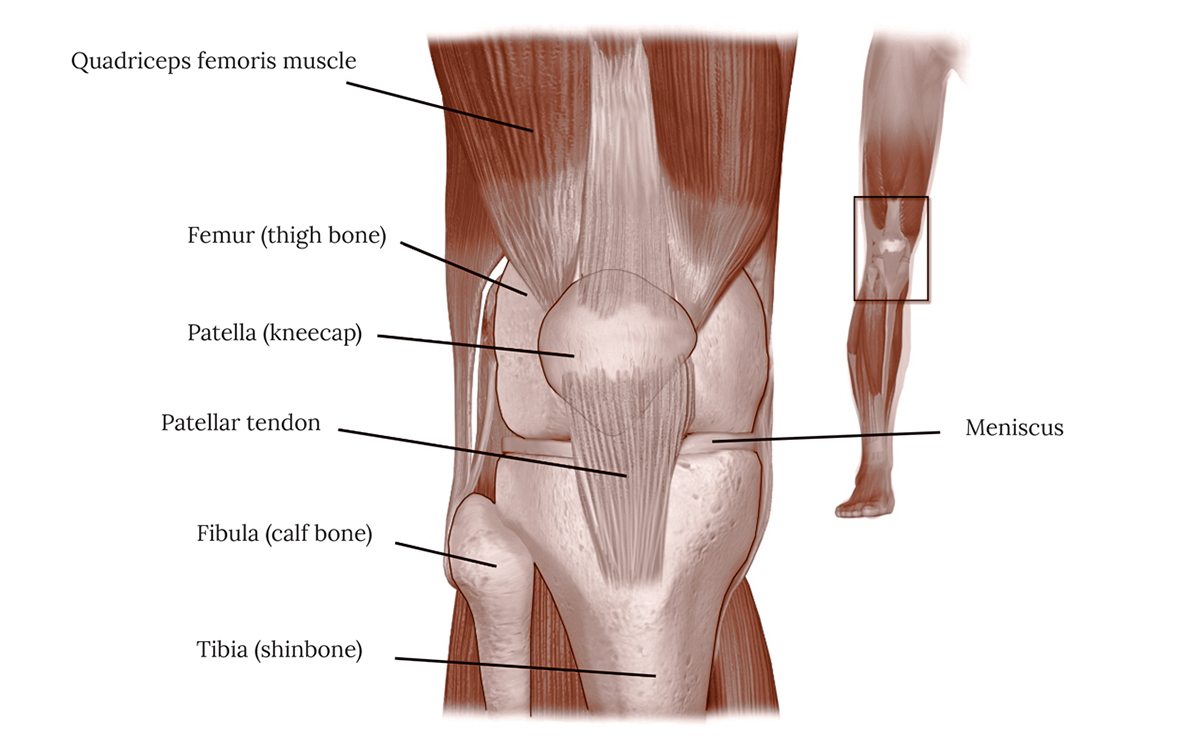

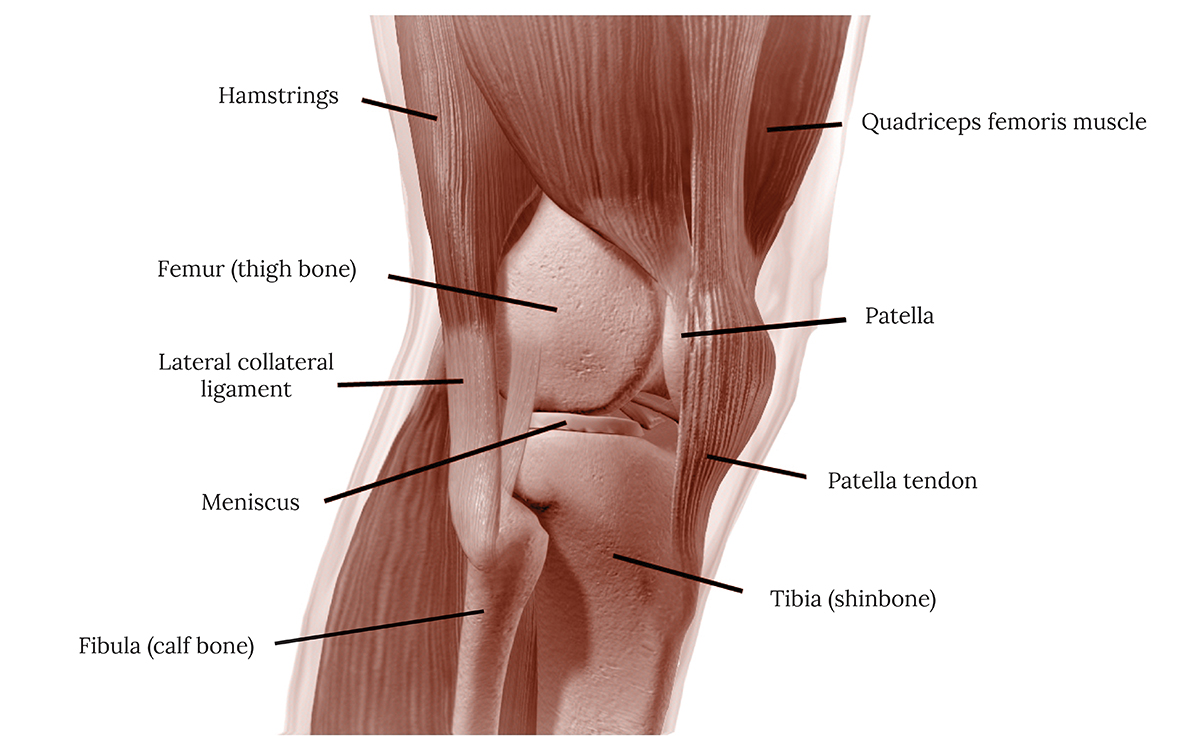

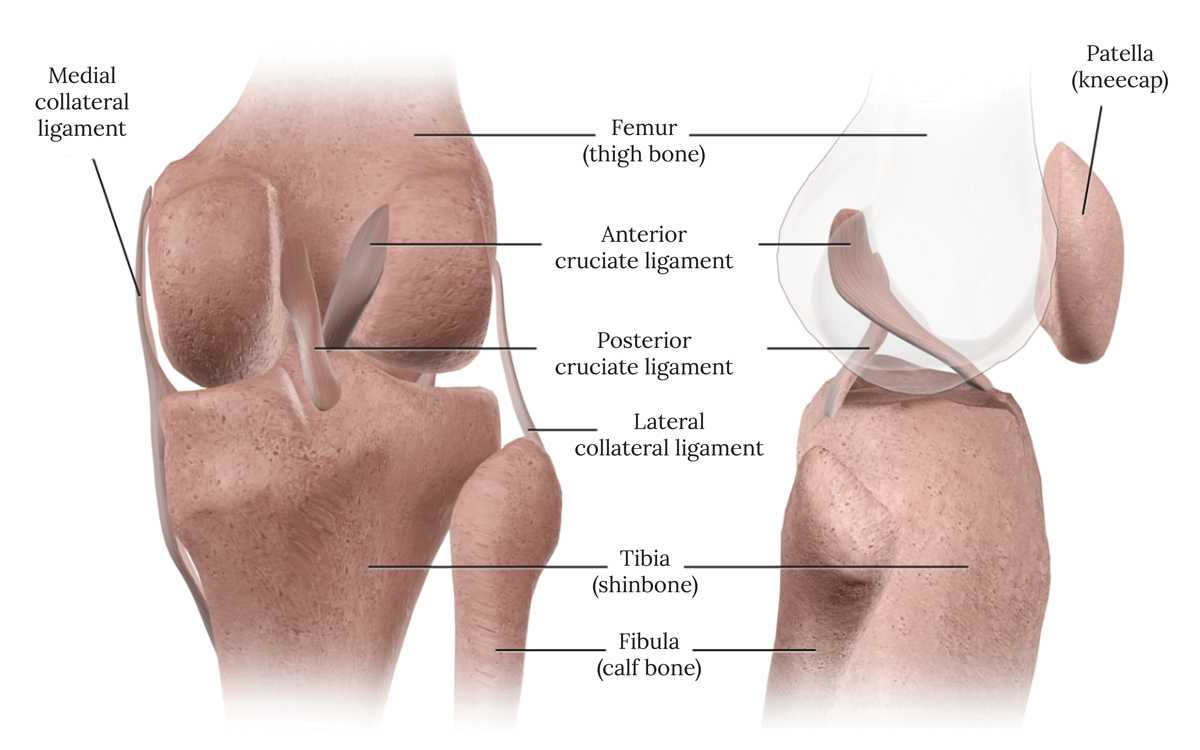

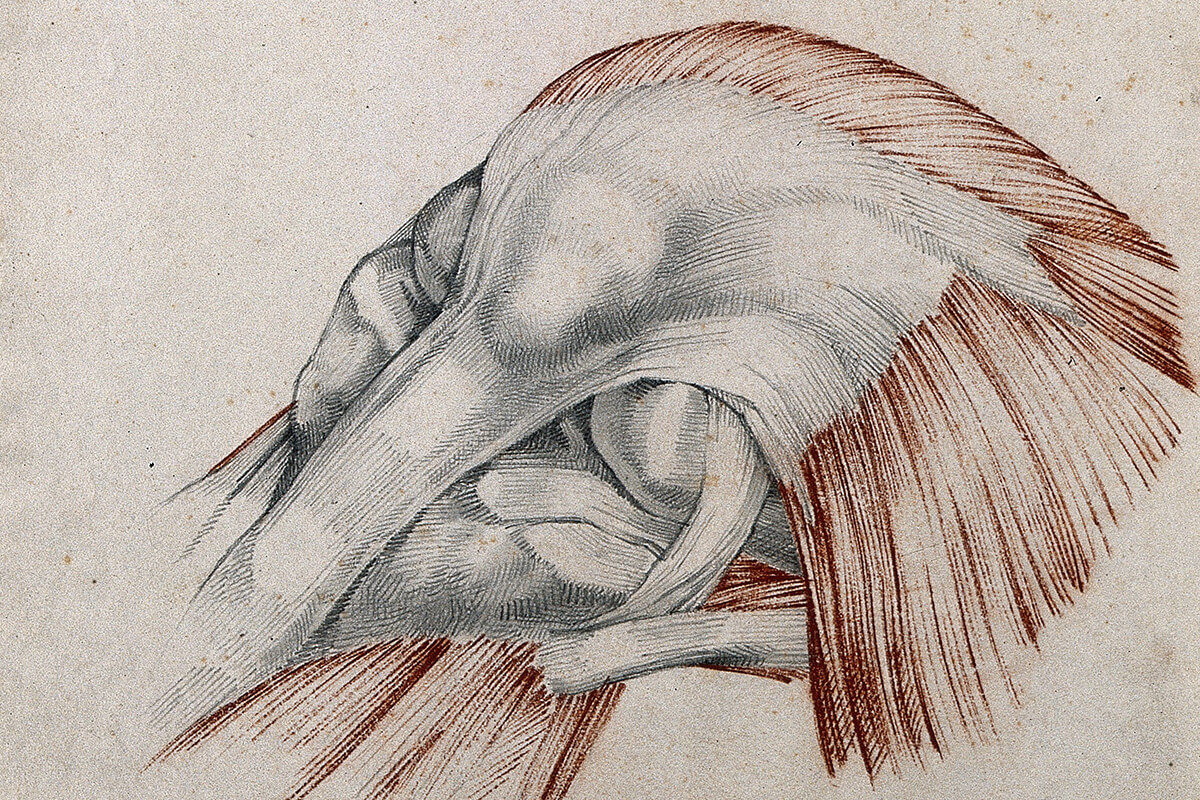

THE KNEE

Mar 15, 2021 in DIS-TANZ-SOLO

After taking an in-depth look at shoulder anatomy, movement and strengthening the other day, this time we’ll look at a common weak spot of dancers: the knee.

As last time, I would like to recommend the two books ANATOMY OF MOVEMENT by Blandine Calais-Germain and STRENGTH TRAINING ANATOMY by Frédéric Delavier to get even more helpful information on the subject. But let’s dive into the topic…