DIS-TANZ DIARY #8

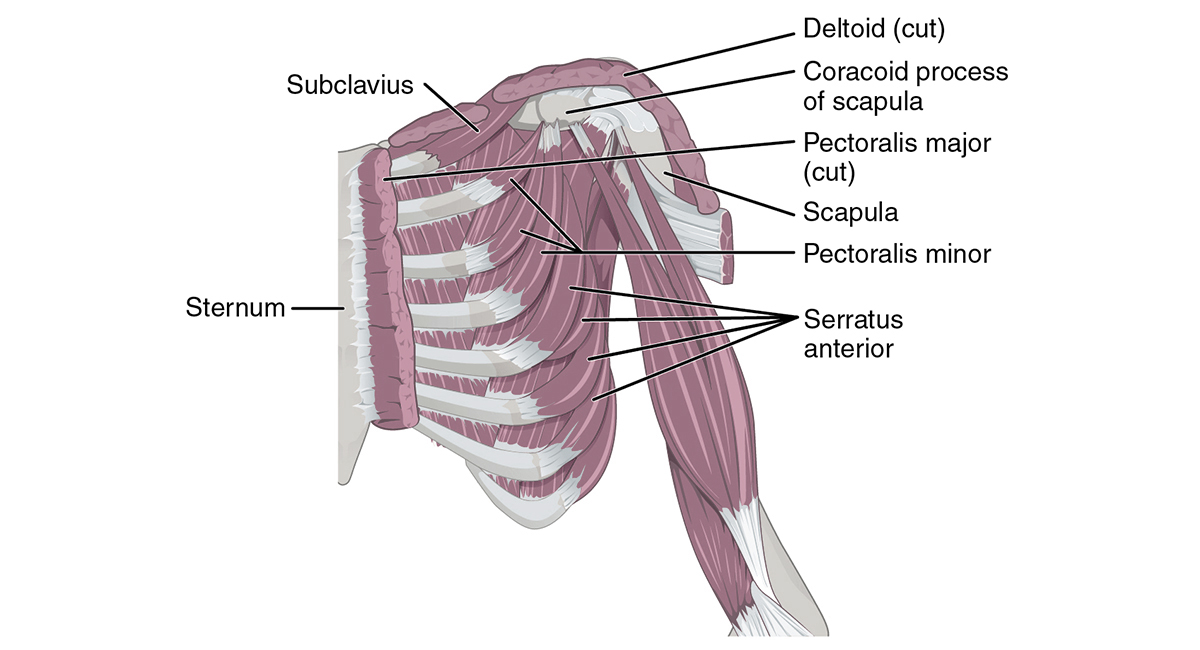

THE SHOULDER

Feb 15, 2021 in DIS-TANZ-SOLO

As I said from the beginning, this diary will be quite subjective and erratic. I’m taking you along on my personal research and learning journey, sharing all the information that seems interesting as it comes.

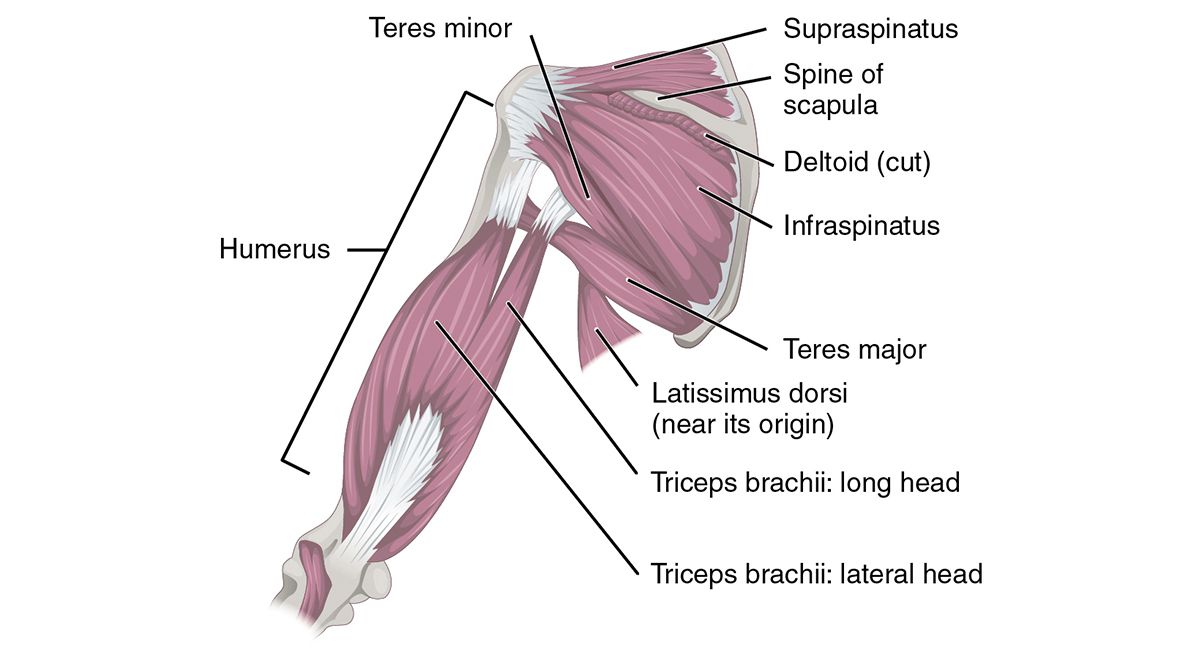

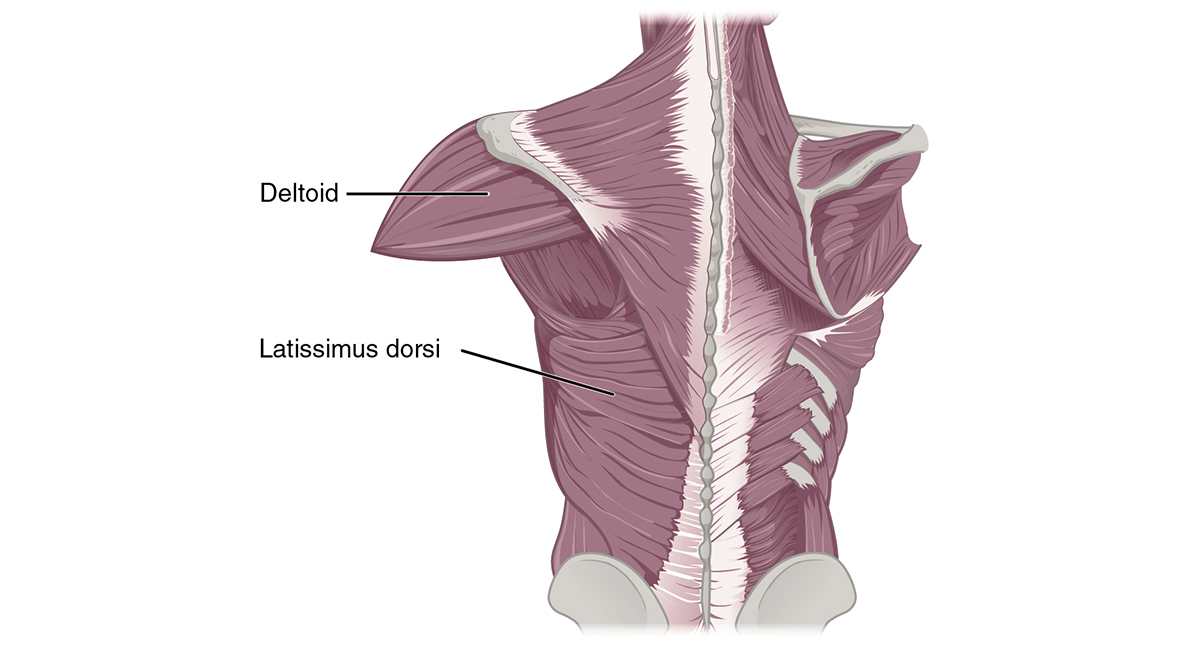

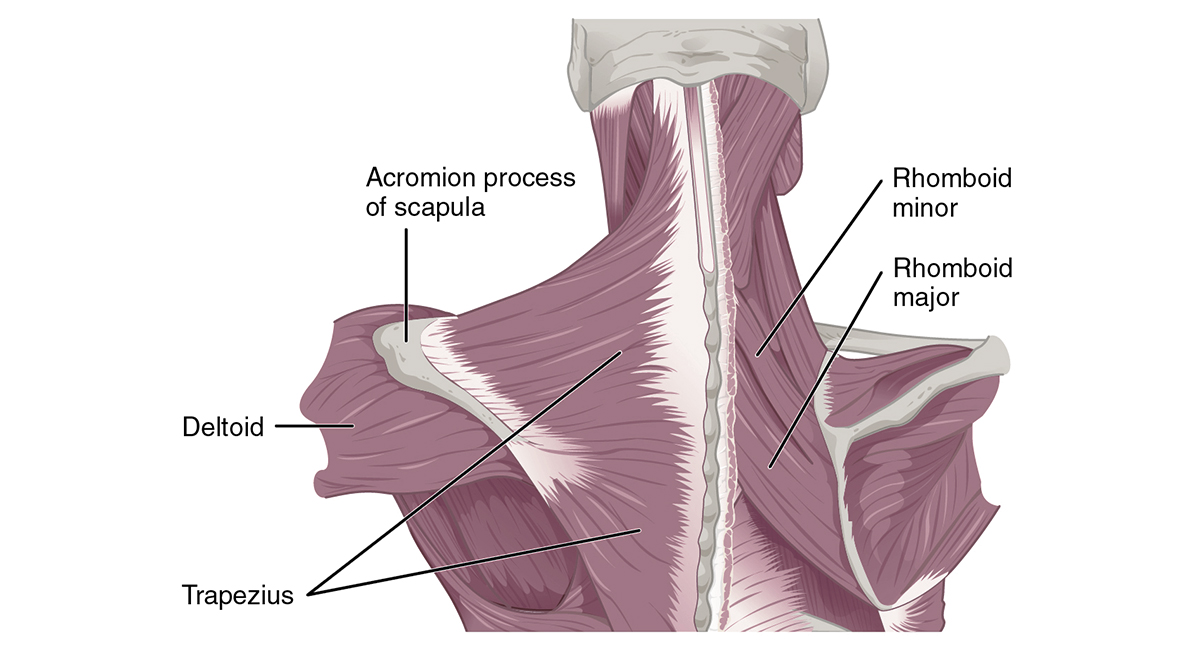

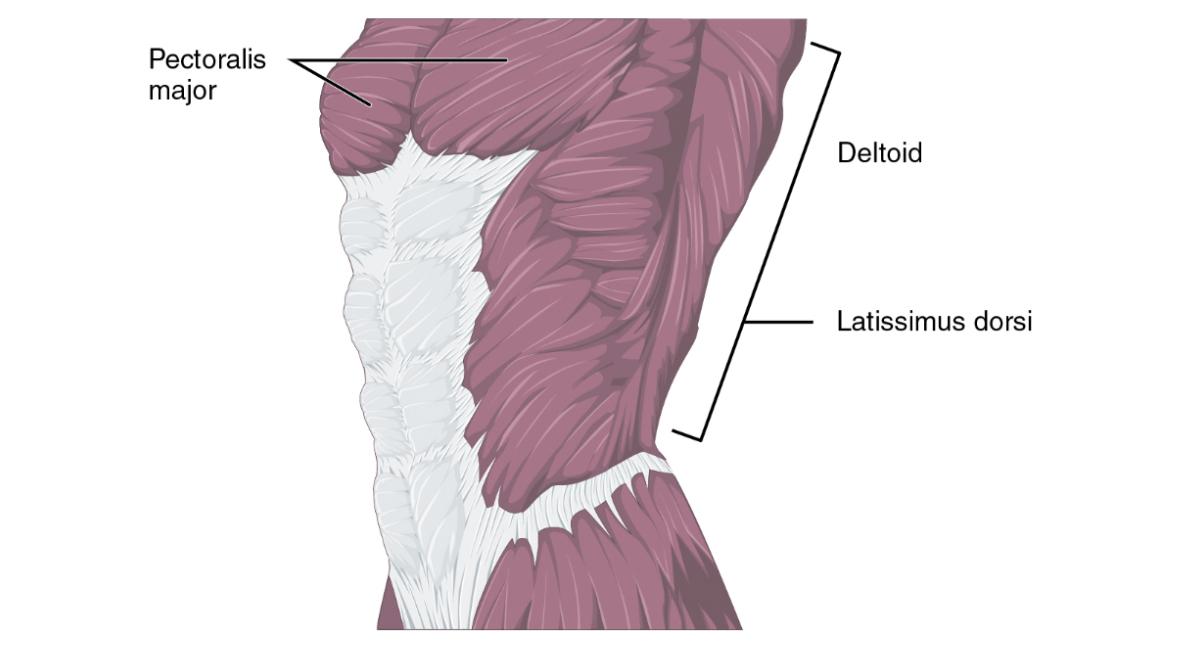

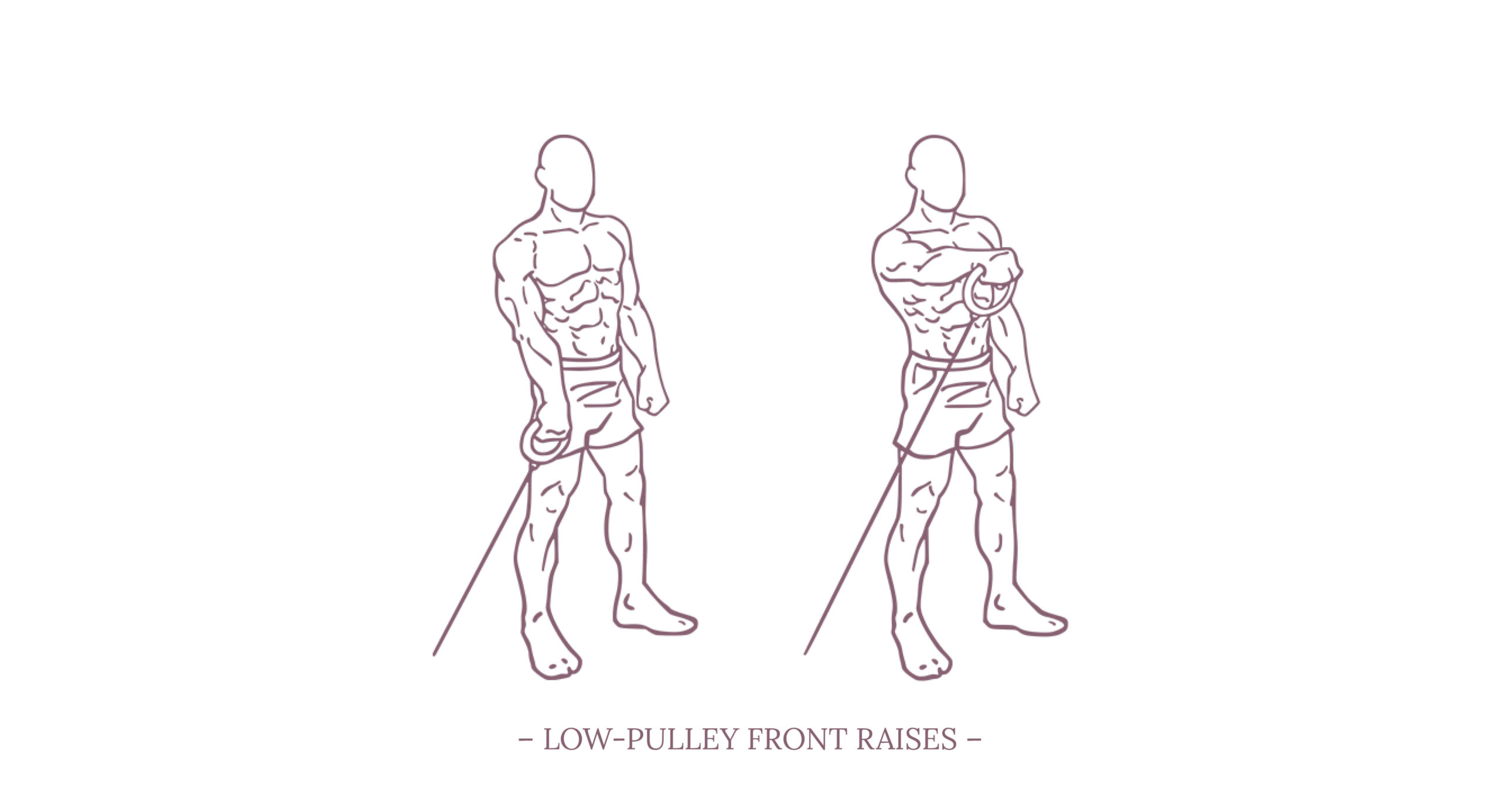

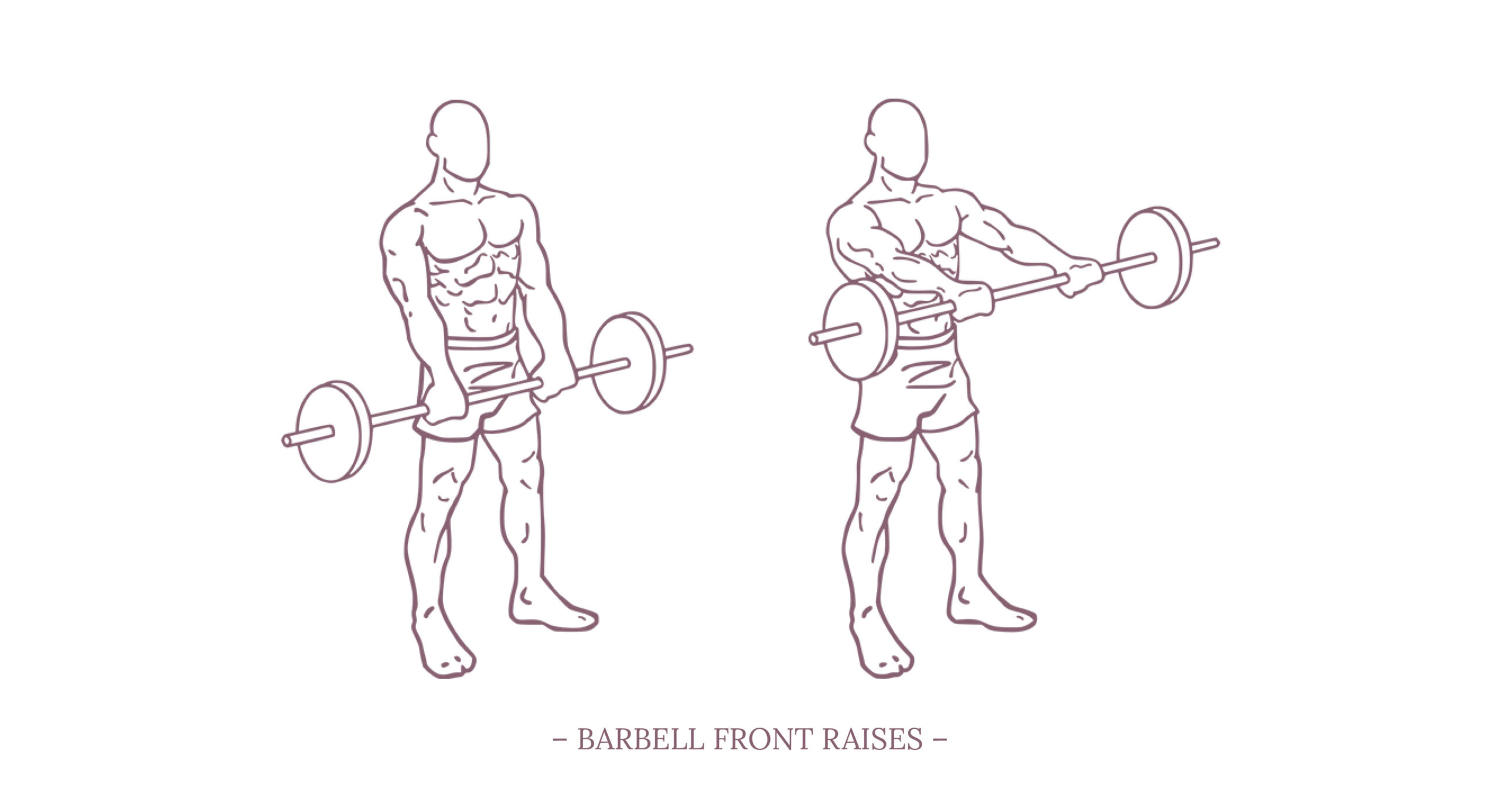

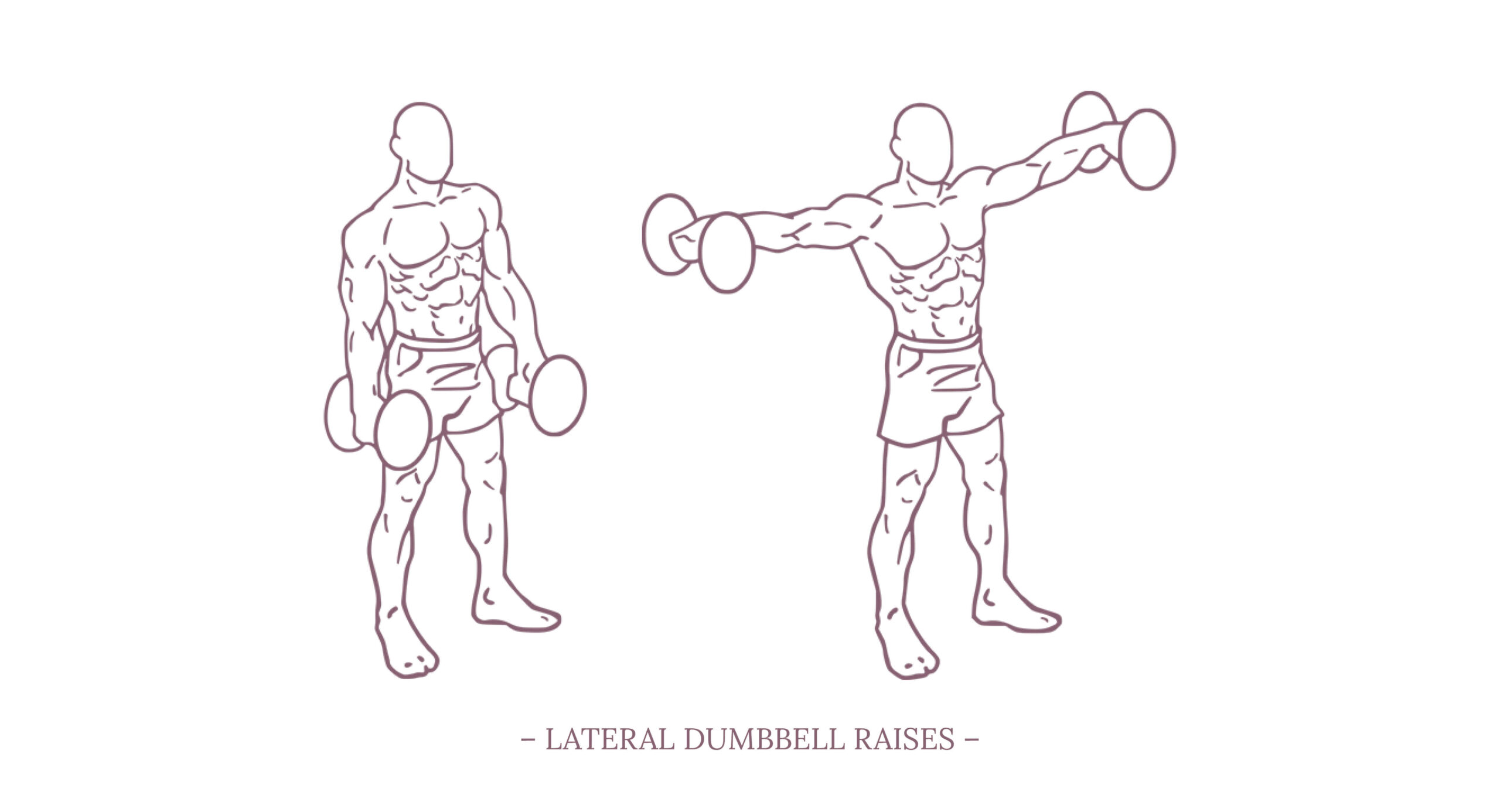

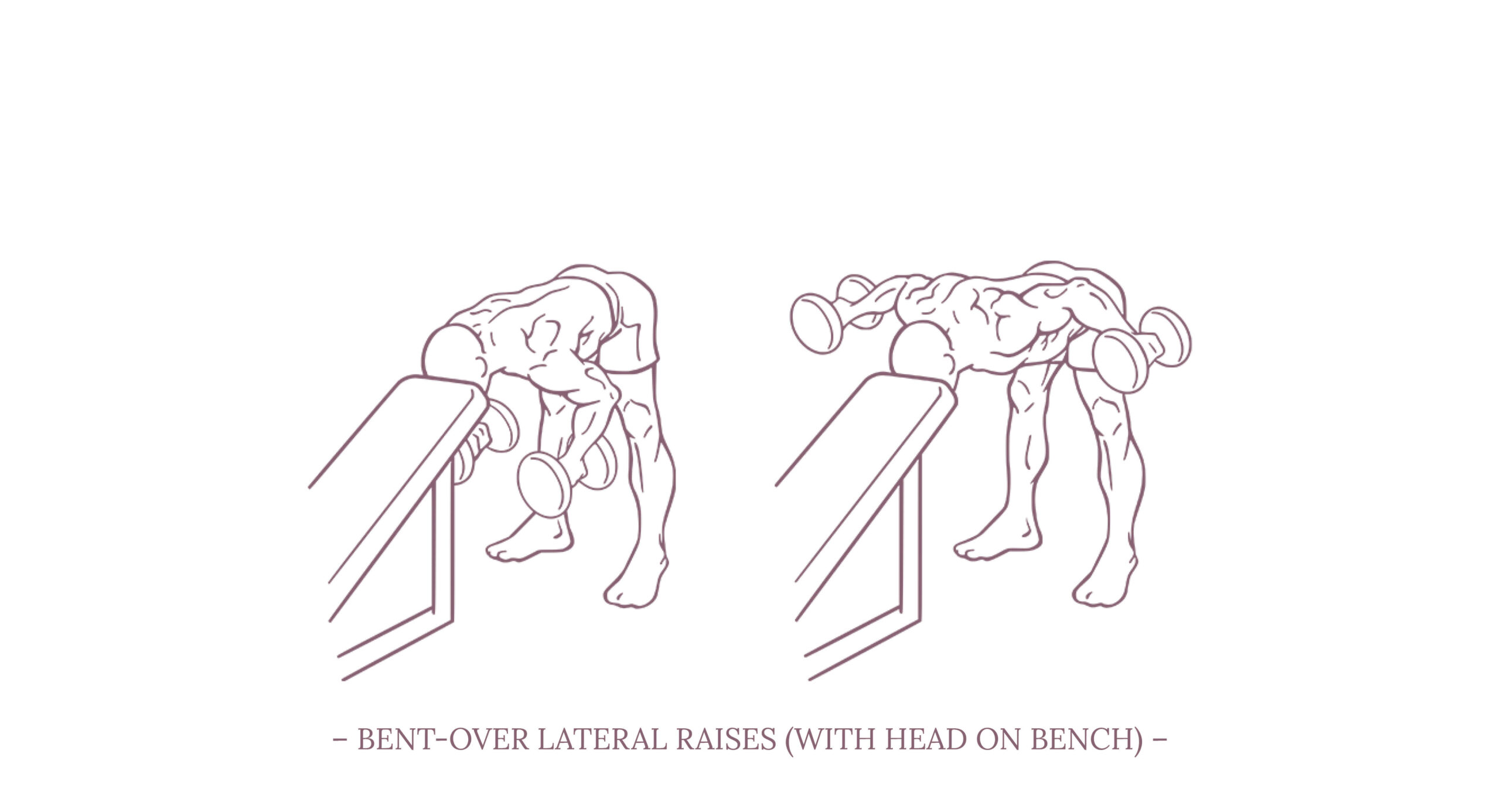

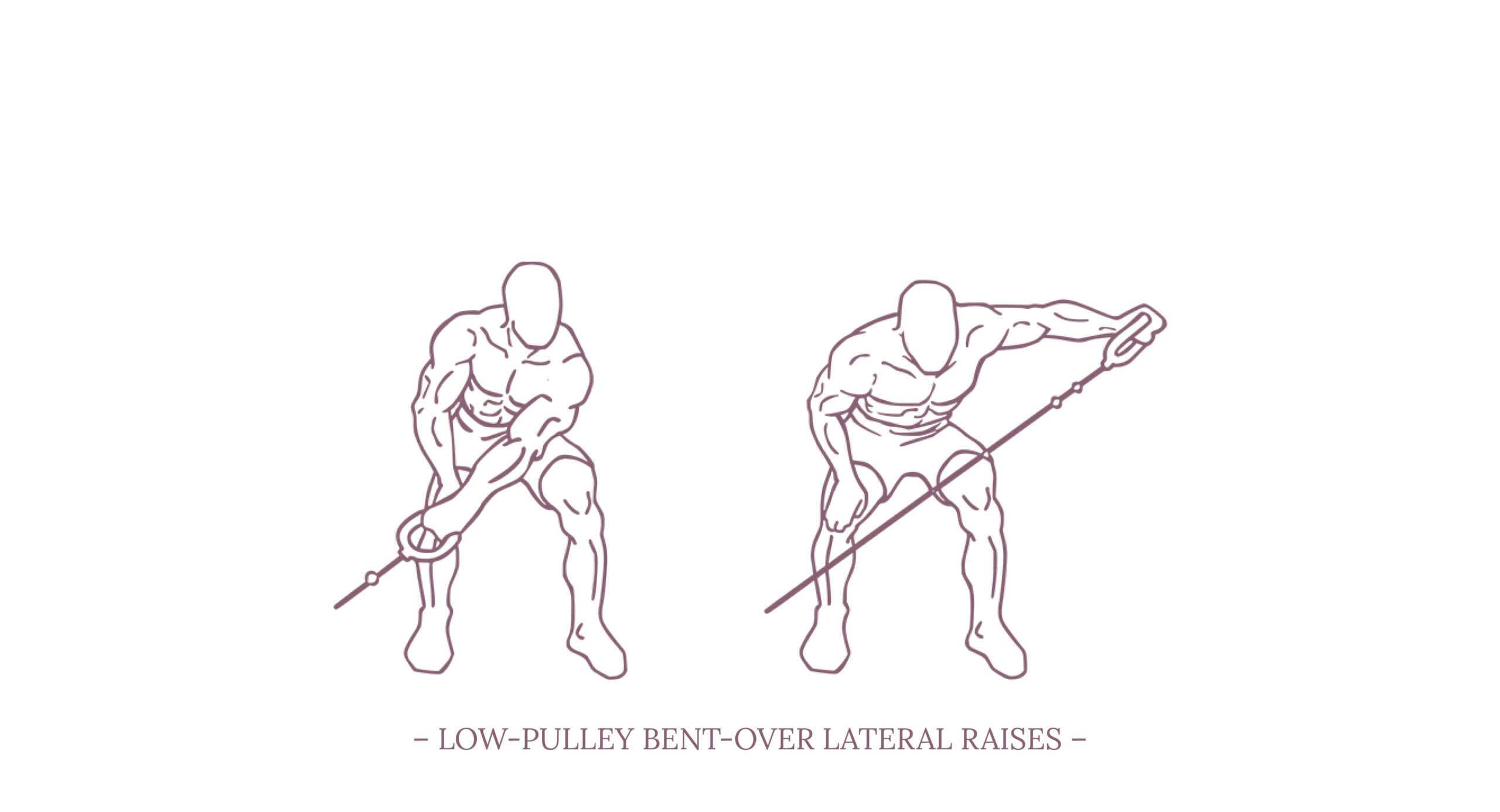

Since I’m currently dealing with the last fades of a nagging shoulder problem, and therefore dealing with anatomy, physiology, and appropriate strengthening exercises, this chapter is a bit of a digression on all things shoulder.

I will focus mainly on the anatomical principles that are directly relevant to our work, i.e. bone and muscle structures, and won’t touch on neurovascular aspects.

If you are looking for more in-depth information on the subject, I highly recommend ANATOMY OF MOVEMENT by Blandine Calais-Germain and STRENGTH TRAINING ANATOMY by Frédéric Delavier. Both books combined give a comprehensive impression of anatomy as well as practical applications that are super useful for our work in the dance studio as well as in the gym.